12th September, 2021

Week 37/52

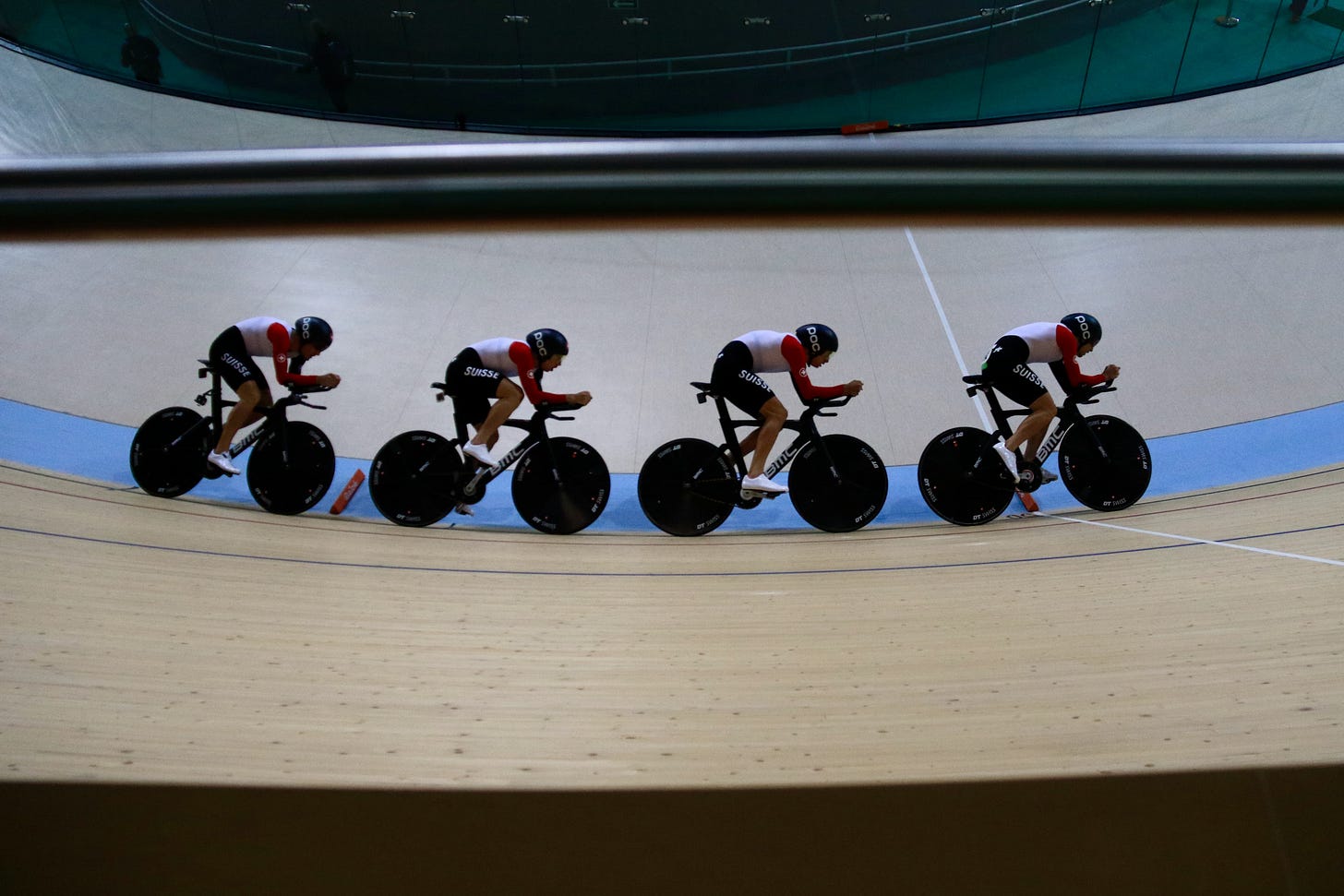

Photo: Swiss Team Pursuit squad, racing at the Rio Olympics in 2016, by me

This week we are going deep into the weeds of start-up compensation, options, capital gains and tax. I hope you're sitting comfortably...

🎖 Reward

Q: How do you split the winnings?

Think about all of the different ways we can get paid for the work we do and the risks we take when working on and/or investing in an early-stage venture:

Salary

We can get paid directly for the work we do. This could either be a fixed salary, or an hourly rate.

Advantage: The amounts are agreed and documented in advance and we always get paid (at least as long as the start-up stays in business and we continue to work on it).

Disadvantage: The amounts are fixed, so there is no upside if things go really well.

Commission

We can get paid a percentage of revenues.

This is common for people working in sales roles, for example, and in that case is normally calculated based on sales made, but there are lots of different possible structures with shades of grey depending on how easy it is to attribute sales and revenues to a specific person or team.

A variation of this is where everybody on the team are paid a percentage of total revenues - e.g. as an end of year bonus.1

Advantage: If we're successful we can earn more, and we get paid immediately (notably ahead of shareholders).

Disadvantage: There is no guarantee we'll make as many sales as we need - especially in the early stages things are often slower than we'd hope.

Shares

Last but not least...

We can own shares in the company.

The one (and only) way to acquire shares in a company is to buy them.2

When a new company is incorporated shares are issued to everybody who invests the initial capital. These are typically very small amounts. At the very beginning a start-up is only worth as much as that capital invested by first believers. Later we can buy shares, either from the company when new shares are issued in an investment round or from an existing shareholder who is willing to sell them.

However or whenever you acquire shares, it always involves an investment of cash.

The two (and only) ways to get a return on that investment are: (a) when the company pays dividends to shareholders from profits (this is exceptionally rare for start-ups, because they are often take many years to become profitable and even then usually prefer to re-invest those profits in further growth rather than payments to shareholders); or (b) when the shares can be sold to somebody else.

Advantage: If the start-up we invest in becomes a high-growth company the value of the shares can increase significantly over time.

Disadvantage: We have to invest cash up-front. It can be many many years after we invest before we get a return on that investment. And there is no guarantee of any return at all - in fact the average start-up returns nothing.3

Gonna make you sweat! 😅 4

Perhaps it seems like there are some things missing from this list (it's true there is one, which I'll discuss below, but it's probably not the one you're thinking of...)

For example, we often hear people working on start-ups talk about "sweat equity" and/or "options", as a way of becoming shareholders without investing cash up-front.

Are they though? 🤨

Both of these things are actually widely misunderstood by employees, founders and investors, in my experience.

In simple terms, "sweat equity" is when we are paid for the work we do in shares rather than cash. That's possible, but doesn’t make them free, because the IRD treats the value of the shares as income, just like a salary, and expects tax to be paid on that amount immediately.

(If you have been given shares in return for work on a start-up and not yet paid tax on those, you should stop reading this newsletter and get some tax advice from somebody who knows what they are talking about).

The obvious downside is that, as we discussed, it could be a long time before the shares generate cash returns.

A better way to think about this type of transaction is to imagine we are being paid cash (and paying tax on that cash amount) and then immediately choosing to invest that cash in shares in the company at the current price.

On the other hand, an "option" is a contract that gives us the ability to purchase shares in the company in the future, for a price that is agreed up-front.

There is a lot of jargon to learn in order to understand options:

Typically options have a "vesting" period. This is the time between when the options are issued by the company and when they become unconditional for the employee. Departing employees usually forfeit any unvested options.

Sometimes there are additional performance criteria attached to vesting.5

Once options are vested employees can choose to "exercise" them at any point before the "expiry" date. That means, paying the company the agreed price (sometimes called the "strike" price) in return for the agreed number of shares.

Remember, shares always cost money!

In the case of options the IRD treats the difference between the price you pay (usually a small amount) and the value of the shares you get as income, just like a salary, and expects tax to be paid on that amount. The advantage of options compared to basic sweat equity is just that they allow the tax bill to be deferred until the point where shares can be converted into cash. But that comes with not insignificant complexity.6

So, to answer my own question: sweat equity and options are not a way to give employees shares without payment, they are just salary disguised as shares, with corresponding tax treatments that apply.

Pay to play

What is the other common way of getting "paid" to work on a start-up I mentioned?

It's actually the reverse: it's volunteering time or even paying to work on a start-up.

This might sound incredible7, but it happens all the time.

For example, whenever a potential investor or other people who just want to help meets with founders to give their perspective and advice, without receiving (or expecting) any payment.

Or, following investment, when an investor becomes an unpaid director of the company or advisor to the founders during the early-stages. They have effectively paid the company to hire them!

The justification for this is not complicated: immediately following investment the biggest constraint is forward momentum, so the best option for investors is to focus on increasing the value of their shareholding rather than on their hourly rate.

This is also common in the non-profit sector - e.g. where we might donate both time and money to an organisation to help them with their work.

This is what I’m talking about when I say that the best founders choose their investors.

Smart investors are prepared to invest handsomely in the opportunity to work with the best founders: generally a little bit of money and a lot of time. And in my experience, it’s the time that makes the biggest difference.

Unfortunately most founders optimise for money.8 This creates a race to the bottom for investors (especially those running venture funds) as everybody competes to offer founders more and more cash on more and more generous terms. What gets squeezed are the potential returns and, more importantly, the time that investors can put into helping to make the outcomes great for everybody.

tl;dr

There are multiple different ways to get paid when we work on or invest in start-ups. We should always stop and think about which of these to optimise for in the short-term and long-term.

Related:

The great rock'n'roll royalty riddle

"If you write a song that's recorded umpteen times, the income will last your lifetime plus copyright, which is 70 years."

But if the songs take shape in the studio, over late nights and conceivably the odd spliff, how do you decide who has written what?

🛤 Align

Q: How do we align incentives in a start-up between those who are being paid a salary and/or commissions and those who are shareholders?

This seems like such a simple question, but honestly: if I could get back all of the days I've spent wrestling with this I'd be much younger!

Despite that, I still think it's a worthy goal. When start-ups go well they can go really well.

For example, if you or somebody you know has made good capital gains on a house or rental property over recent years, just quickly do the maths on a company like Xero: When it listed in 2007 the whole company was valued at $55 million (and there were a small group of us who invested prior to that at even lower valuations!) Today it’s valued at $23 billion.

Ideally, when that sort of result is achieved, those who do the hard grind day-to-day to grow the company should share in the upside, rather than having that captured entirely by those who contributed capital.

While it might, on the surface, seem contrary to their own interests, smart investors understand that getting this right is often a key that can help to unlock that upside in the first place. For example, it's common for venture investors to insist on 10% or more of the company to be set aside for allocation to employees via an ESOP (Employee Share Ownership Plan) in any investment round.

So, the question then is just how to manage that allocation.

But the details get devilish very quickly. Often because of tax.

The first problem, as we saw above, is that shares have a cost and we can't just gift them to anybody without creating an immediate tax liability. Meanwhile the payback could be many years in the future, if at all. Generally people are not happy to pay tax on income that may never actually be paid.9

When I first started investing in start-ups it was common to try and solve this using an employee trust structure, which effectively gave employees the benefits of shareholders without them having to invest cash up front. However, there is no such thing as a free lunch - these schemes were very expensive for the company (which is another way of saying "for those who did invest cash") because of the tax that was paid on behalf of employees; because of the cost and complexity of administering them; and, not least, because of the large amount of time spent explaining these schemes to employees (I personally spent a stupid amount of time on this at Vend and Timely, which surely would have been better spent actually trying to grow the business).

For all of these reasons, and others, those schemes were more recently nearly all replaced by simple options schemes.

Another alternative, which is growing in popularity, is called "phantom equity". This is just a fancy name for a cash bonus which is paid in pre-agreed circumstances - e.g. when a start-up is floated on a stock exchange or acquired. The tax position on these is cleaner, or at least more easily explained: employees pay tax on the bonus when it’s paid, just as they would on any other salary amount.

(Perhaps as an indication that I've completed a full lap, this is a throwback to the exact pattern we used at Trade Me following the sale to Fairfax in 2006 - only a couple of us still working on the business at that point were shareholders, but everybody who was an employee or contractor at the time of that "exit" received bonus payments, funded by the selling shareholders, that were staggered over the two-year period of the earn-out).

However, as we've seen, neither of these solve the real problem: investors who pay cash up-front for their shares pay no tax on their gains when those shares are sold (because in NZ there is no capital gains tax on investments10), meanwhile employees who receive options or bonuses that are paid on exit as part of their compensation are taxed at normal income tax rates.

Investors and founders both want employees to be shareholders, to align incentives. But it’s impossible to do this in practice. Employees don't and can't benefit from the gains in the exact same way as investors do.

As others have noted, there are two possible solutions if we want to close that gap: remove the tax on employee gains, or impose a tax on investor gains.

Occasionally people in the ecosystem agitate for special tax treatment for start-up employees, but they are always curiously quiet about capital gains tax for start-up investors.11

I've also yet to see any proposal that doesn't just simplify to "we'll just pay less tax, kthxbai". There is always a frustrating lack of detail about how this would be justified and explained to other tax payers, who would be left covering the difference.

Remember Hugh the forklift driver from Timaru who I wrote about earlier in the year. How would tax breaks for start-up employees benefit him and his whānau? I'd love to see these arguments focus more on the anticipated collective benefits that tax breaks might deliver - i.e. less what the government can do for start-ups and more what start-ups can do for the government.

Perhaps we think these incentives would create more highly paid jobs or more profitable start-ups that contribute income tax back to the economy. Or perhaps we could argue they would increase productivity, because employees working on start-ups would be more motivated.12 If we believe those things are real then let's spell them out!

(To be honest, I'm not convinced they are real. These arguments often sound a lot like trickle down economics. As I’ve argued: we don’t know what we want, but we’re determined to get it!)

So, is a capital gains tax is the solution...?

🔁 Loop

Q: What would it take to convince more people to invest in start-ups rather than rental property?

A common answer to that question is: a capital gains tax.

I'm skeptical. Let me try to explain why...

The fundamental problem with the housing market is that currently nobody believes that prices will fall. The issue is not that capital gains on property are tax free. It’s that everybody believes that capital gains on property are almost certain.13

This explains why people are not so enthusiastic about other types of capital gains, which are also tax free - e.g. gains on investments in businesses.

In those cases the capital gains - and indeed the capital itself - are at risk.

So, it's difficult to see how a capital gains tax would make much difference to how capital is allocated. Especially if it also applied to other types of investment. Especially especially if there are exclusions related to housing - e.g. family home is excluded.14

If we want to shift investment preferences - e.g. less into property, more into productive businesses - then we need to make those things we want to encourage either less risky or more rewarding.

If we want to make housing more affordable then we need a solution that causes prices to fall.

But nobody wants their property value to fall, so any solution that would cause that to happen is considered politically impossible.15

Which takes us back to the beginning of this logical loop...

The fundamental problem with the housing market is that currently nobody believes that prices will fall.

The issue is not that capital gains are tax free. It’s that everybody believes that capital gains on property are almost certain.

Related:

What can our discomfort teach us about how we deal with risk or learning a new skill? It's all about thresholds and tolerances...

Top Three is a weekly collection of things I notice in 2021. I’m writing it for myself, and will include a lot of half-formed work-in-progress, but please feel free to follow along and share it if it’s interesting to you.

This is also how partnerships work.

Okay, maybe you inherited your start-up shares or won them in a late-night poker game, but even in those contrived cases somebody bought them in order to be able to gift them to you!

But, remember, when it comes to investing in start-ups, averages are not useful.

Did you listen to the podcast I linked to a few months ago about Milli Vanilli yet? If not, you don't know how C&C Music Factory fit into that crazy story. 🤪

Recently I've seen examples of options which vest based on milestones rather than time. As always, there are pros and cons with this approach.

The mechanics of this, if you're really interested, typically involve options that have a very low (i.e. nominal) strike price and a long-dated expiry (i.e. 10 years), so once options have vested employees can just sit on them until there is a transaction and then exercise them and sell them immediately. The tax bill in this case is on the difference between the strike amount and the sale price, which can be ... substantial. But at least employees have cash on hand at that point to cover that bill.

Or as we might say in NZ: fairly interesting.

To be fair for a whole generation we’ve been saying this is the hard part by promoting the idea that there is a shortage of capital.

One of the unexpected lessons of the last year for me is that even when they are paid significant amounts that have been deferred using options, some people are still not happy to pay tax on that income. I guess this is a concrete example of the research about how happiness attached to income and wealth is at least partly relative. ¯\(ツ)/¯

If you ever find yourself talking with a US-based VC, I’ve found you can very quickly and easily make their brain melt by explaining to them that the capital gains tax rate on venture investments in NZ is 0%.

While this isn't true if you are a trader rather than an investor, it's practically impossible to trade in early-stage venture investments, even if you wanted to, because they are incredibly illiquid - and often remain that way for a long time (sometimes forever!)

Everywhere else in the world investors expect to pay tax on capital gains. And, it’s fine: that just gets priced into valuations and stock option calculations.

I have to call out this nonsense specifically:

"The challenge for New Zealand economy is, of course, that we have a capital gains-free part of the economy in the housing sector, and productive capital that goes into businesses - whether it's your own business or whether you're investing in someone else's business - doesn't get the same rewards,"

Source: The Icehouse's David Downs, Gavin Lennox on how Govt can help startups

That’s just simply incorrect. The housing sector and the “productive” business sector are both treated exactly the same - there are no capital gains taxes for investors in either case.

And, as per the Xero example I referenced, the tax free capital gains on start-up investments can be much greater than from property, if you invest in the right companies.

The big difference between investing in property and investing in start-up is that property investments can be leveraged.

On motivation: I don't believe that employee share ownership is a useful way to motivate a team. I've never seen that happen in any of the schemes I've helped to implement. In fact the opposite - many people discounted the value of the shares they were given to zero because they weren’t sure they would ever be valuable.

The thing that actually motivates people is a company with a purpose they believe in, work that they find meaningful and colleagues who support and encourage and challenge them to be better.

The reason to implement an ESOP scheme is so that everybody who contributed gets to share in the success if and when it happens.

Historically people ranked good deeds based on what was considered most likely to get them into heaven when they died. Now we rank property purchases based on estimated capital gains. Same logic, I suppose.

Westpac chief economist Dominick Stephens hit the nail on the head in this article (which is now more than 5 years old):

People want everyone to be able to buy a house and the financial system to be safe and they don't want to see house prices fall, and they don't want to see infill in their suburb.

Well something has got to give. The resolution is going to involve someone experiencing some disappointment relative to what they'd hoped for.