24th June, 2024

If "tech" is the answer, what is the question?

Today I presented the opening keynote for the SportNZ Connections Conference in Auckland. The theme this year is “Innovate to Elevate“. As anybody who has followed my writing over years will know, the intersection of technology and sport is my happy place, so it was a privilege to be asked to present to this group. For everybody in the room who wants to follow some links, and for everybody else who might be interested, I thought I’d also share some of what I said here.

As always, I’d love your feedback…

People seem to be much more anxious than excited about technology these days. Some of you may even consider technology to be the enemy. We need better questions to ask about technology, and how it could be applied to our organisations and teams.

We can start with a simple one…

Q: What is “technology”?

It seems like a simple question, right? What’s your definition?

This is my favourite answer, from Alan Kay, one of the legends of Computer Science: 1

Technology is everything that was invented after you were born.

Everything else is just stuff.

I’m more interested in stuff. The stuff we already have. The stuff we could make better use of. Some of you may not even consider it to be “technology” any more.

Here’s another:

Technology is everything that doesn’t work yet.

When we think and talk about technology, it’s very tempting to get carried away in the future, and hypothesise about all of the things that don’t exist yet, or at least don’t quite work yet.

The sports sector says it’s focused on tamariki and rangatahi - children and young people. In that case, there is an obvious but important distinction to keep in mind: they were all born more recently. So, their definition of what is stuff and what is technology is very different from yours and mine.

Rather than starting with the future I want to begin by looking back at the three mega-trends from the last 20 years or so, and the dominant business models that have emerged in that time. Then we’ll finish by thinking about the next wave.

⏮️ Part I: Three Tidal Waves

Rather than worrying first about the future I want to look back at the three technology waves that have washed over us during the last 20 years or so, and understand the lessons from those.

Starting with the most important trend of all…

1. Smart Phones

The smart phone revolution started in January 2007 when Steve Jobs and Apple launched the first version of the iPhone.2 Look at it in his hand … it’s tiny!

The clean-out this technology wave has caused is so thorough it’s hard to remember what start-of-the-art was like before that. So rewind to March 2006, less than a year before the iPhone launch, to the month that Trade Me was sold. This is the Nokia 3210 phone that I used every day then.

Looking at it now feels a bit like looking at ancient tools in a museum display case. Nokia was one of the companies that used to dominate mobile phones, along with competitors like Motorola and Ericsson. Those three are now all owned by other technology companies.

Perhaps you were lucky enough to use one of these. Just like Nokia, Research In Motion, the company who invented Blackberry is no longer, having been acquired by TCL - an obscure Chinese electronics brand.

Smart phones have arguably been the most successful technology ever. Previous technologies, like washing machines, cars and telephones, all took 20-30 years to reach 80% adoption. Smart phones achieved that milestone in half that time. And in the process obliterated the technology that preceded them. By 2019 fewer than 50% of US households still had a landline telephone.3

In NZ, by June 2023 there were fewer than 70,000 residential voice-only phone connections remaining (and that number was down 24% on the previous year).4 Meanwhile there are 5.9 million mobile connections - more than one per person. Collectively we spend just shy of $3 billion per annum on those connections (not counting the cost of the devices themselves). 43% of that is pre-paid.5

We can also look at usage. Trade Me numbers give a pretty good proxy for that. They report now nearly 60% of traffic from mobile phones. That’s up from 30% in 2018 - it’s nearly doubled in that time.6

This is how we’re all choosing to use technology.

The School Census from last year gives a pretty good indication for younger people. That found that 69% of Year 9 students had their own mobile phone, and that increases to 98% for Year 11 students. 7

(Those are Form 3 and Form 5, for those of you still counting school years using the Imperial system!)

Recently there has been a lot of debate about use of technology in schools. But this handwringing is nothing new.

When I was a student this was the state of the art in technology…

The Casio FX-82super. It could do fractions! Mind blowing!

Back then parents and teachers worried about the technology gap created by calculators like this. They were banned from exams. We had to do our fractions the way that God intended - using a pen and paper.

Go back a few years earlier than that when I was in Year 9 / Form 3, and these two pieces of technology were on the compulsory stationary list…

They used to be technology, right? Then they became stuff.

This is a global trend. This is a photo I took in Rwanda - in Africa even the statues have their own mobile phones!

In the heyday of Microsoft, in the 80s and 90s (the “late 1900s” as my kids call it) Bill Gates would talk about his dream of having a computer in every home. Now we have a much more powerful computer in every pocket.

75% of adults have a smart phone. But, what do we do with them? The answer is: Everything.

Close to three quarters of all the adults on earth now have a smartphone, and most of the rest will get one soon. However, the use of this connectivity is still only just beginning.

The last time we collectively spent more time watching television than using our phones was in 2018. Since then screen time stats have become blended - because amongst other things, these devices have completely changed the way we all consume television.

When combined, the numbers get really big: on average we each spend about 6 hours and 58 minutes per day looking at a screen.

Some NZ stats, from NZ on Air’s 2023 “Where are the Audiences” media survey…

In 2014 80% of the population 15 years and older watched broadcast television. That’s dropped to 50%. And even that number is skewed by age. For those 60 years and older the number is still 75% but for 15-39 year olds it’s only 30%. 8

During the same period, online video reach has increased from 30% to 68%.

The most interesting result in that survey for me is when people were asked to nominate their favourite channel. 34% said TVNZ. 44% said YouTube.

Q: What is a phone?

At the launch in 2007 Steve Jobs described this new product as the combination of three separate devices:

An iPod

A mobile phone

An “Internet Communication Device” (his words)

Fast forward to today and for many of us “Phone” is the least used app on the phone. The ability to make voice calls isn’t the killer feature.

There are three things that actually make these devices remarkable:

The Screen

We talk about “screen time”, but what about the screen itself? Looking from the outside a smart phone is nearly all screen (we will talk about the little notch at the top in a second).

The way we interact with these devices is personal - much more personal than so-called personal computers. We touch them directly. It’s intimate and tactile.

And, intuitive. If you hand a baby a phone they know what to do with it - they touch it.

These screens have also gotten much better since 2007. This is how many pixels there were on the first iPhone screen - compared to the current screen resolutions…

These screens are our interface to the world.

The Cameras

The addition of photos and videos to these devices has enabled a whole new layer of applications - video chat, image recognition, and augmented reality, not to mention selfies.

In just a few years this completely changed how we behave when we are together.

How many of you are holding your phone in your hand right now?

If I asked you to turn it off completely, how anxious would that make you feel?

If your phone buzzes while you’re reading this will that prompt you to look at it (and if yes, then what does that say about your priorities?)

The Sensors

Last but not least, it’s the sensors that makes these devices really different from the computers that came before them. They are no longer just processing text and numbers. They are aware of the world.

Some examples:

GPS, Accelerometer, Barometer & Gyroscope - combine to make the device aware of your position and movement

Proximity - so it can tell when it’s been held to your face (or how far from your face it is)

Identity - using fingerprints or iris/facial recognition, so it knows you are you

RFID - so it is a secure credit card, and also potentially replaces other things that used to be separate physical cards, like transport passes and hotel keys

Microphone - so it can hear your voice and the environment around you

Moisture - so they can tell if you’re being honest when you take it in for a service after dropping it in the toilet

The enabler of all of this is the miniaturisation of electronics and huge economies of scale due to how many of these devices are now manufactured.

You may have heard of Moore’s Law. This graph goes all the way back to the 1970s when there were 100s of thousands of transistors on a chip, to today when there are 10s of billions. It appears there has been steady progress throughout that time. And there has been. But it’s logarithmic.9

If we plot that same graph on a linear scale you can see the phenomenal growth that has occurred since the launch of smart phones in the early 2000s.

This has an impact well beyond just phones.

An Alexa is really just a smart phone with no screen, but with better speakers and microphone.

A Fitbit is really just a small phone you wear on your wrist, with extra sensors - for example to track your heart rate. Smart watches can now even do an EKG and predict if you’re about to have a heart attack, or automatically call emergency services when it detects you’ve fallen or crashed.

In a sporting context, we now have GPS trackers sown into the back of every rugby jersey. Our high performance cyclists and rowers use data loggers to track real-time performance and training data.

These things are all using the same miniaturised electronics. Phones have made that orders of magnitude cheaper.

However,

We are now past peak new phone. Since 2018 the number of new devices being sold is no longer growing each year.

Perhaps you still think phones are technology. But to the next generation mobile phones are definitely now stuff.

All technology follows an “S-curve” like this - when we get to the stable part of that curve we stop talking about the thing and start talking about what we can build on the platform created by that thing. Which leads nicely to…

2. Social Media

The social media revolution started a few years earlier still in February 2004, with the launch of TheFacebook (as it was then called). This wasn’t the first social network. If you’re old enough you may have used sites like MySpace or Friendster. In the very early 2000s I had a hand in building Old Friends, which was Trade Me’s social network - a reasonably shameless copy of a popular UK site called FriendsReunited.

But Facebook became the most used. In 2023 they topped 3 billion monthly active users for the first time.10 I think we can fairly say a business is dominant when we can directly compare the size of their customer base to the global population.

The company behind this also got very large - growing to nearly 90,000 employees (at least that was before last year, when they cut 19,000 people).11

Global social networks have achieved massive scale. The top six on this list all count monthly active users in the billions.12

1, 3, 4 and 7 on this list are all owned by Facebook.

The thing they all have in common is they are platforms where people can publish and share their own content.

Consider TikTok, which is the fastest growing network on this list. Actually, it’s also on the list twice. Douyin is the Chinese version of TikTok. Or, more accurately, it’s the other way around: TikTok is the non-Chinese version of Douyin.13

TikTok has been so popular that other networks have been forced to respond with their own similar services - Instagram Stories and YouTube Shorts, for example.

They have grown from 500 million monthly active users in 2019 to over 1.6 billion today.14 Instagram might disagree but I would say they are the first truly mobile social network.

As well as counting people we can also measure time spent using these sites.

A social network many of you may not have heard of is Twitch, now owned by Amazon. They pioneered video streaming, and built a network where anybody can host or watch live or delayed video streamed by other people on the network - predominantly people playing computer games.

One day my father was watching my son use Twitch and got frustrated

“Why don’t you play your own games, rather than just watching other people play games?”, he asked him.

“Grandad, you’ve spent all morning watching golf on Sky!” was his excellent response.

Whatever you think of sites like this, usage has exploded. Watching people play computer games is now much bigger business than ESPN.15

Here are some numbers which shocked me when I first saw them:

This is the number of people who watch each of the major leagues in the US. The big four are football, basketball, baseball and ice hockey. The number of people watching e-sports is already greater than baseball and ice hockey.

These are numbers from … 2017. So project forward another 7 years.

To put those numbers in perspective the global audience for the Rugby World Cup final last year was about 94 million people.

Also in 2017, was the launch of the popular online game Fortnite. By April 2019 they had over 300 million users. That has increased to 400 million today.

You might not count this sort of game as a social network. But consider that a key element of game play is the live chat and collaboration between people playing at the same time. If that’s not a social network, what is?

Another sporting example, my favourite social network: Strava. This is an app which allows you to track and share your runs, bike rides and other workouts. Again, on the surface it doesn’t present as a social network, but social features like feedback and leaderboards and group challenges are woven throughout. They use the GPS data you upload to connect you with other people who were running and riding at the same time. The net result is a delightful and encouraging network of people with related interests.

As it stands, this is the only sports “club” that I currently pay to belong to.

It’s used all over the world. This is a heat map of all of the places where people have uploaded activities to Strava. You can see New Zealand is well covered.

A couple of years ago some US soldiers in Afghanistan got into trouble when runs they posted to Strava inadvertently disclosed the location of their secret base.16 Oops!

Q: Are social networks good or bad?

There is a growing negative sentiment about social networks. The biggest concern, amongst older people, is privacy.

Actually there are worse things to be worried about:

The great promise of the Internet was that more information would automatically yield better decisions. The great disappointment is that it actually yields more possibilities to confirm what you already believed anyway.

— Brian Eno

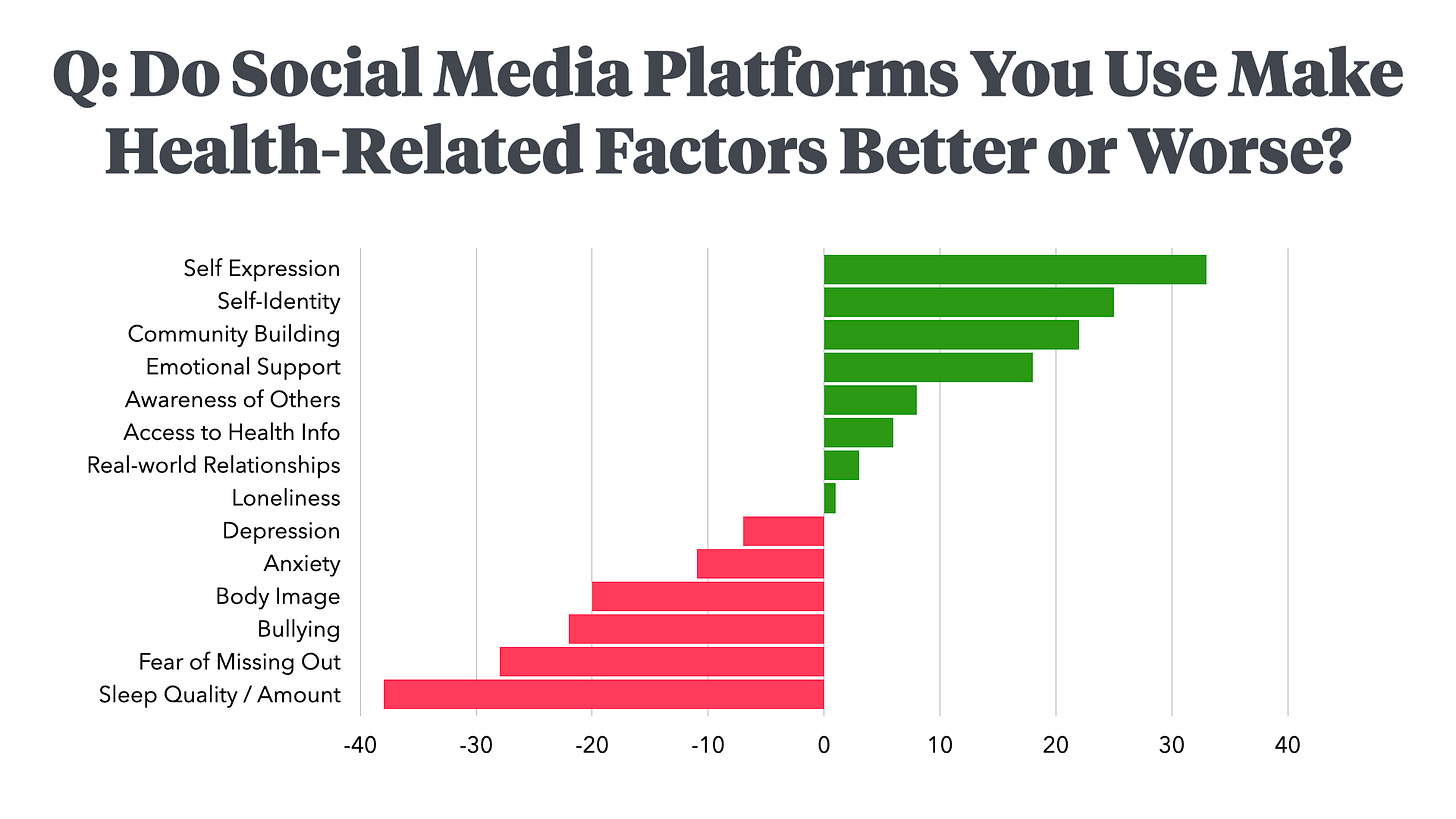

The reality is social media amplifies the good and the bad. They are great platforms for self-expression and self-identity, and allow anybody to build communities of like-minded people. But at the same time they have a terrible cost in terms of anxiety, bullying, not to mention sleep.

However you feel about social networks, you can’t deny:

They spread messages very quickly

They let anybody do this

Increasingly these networks set the agenda of mainstream media.

In the flag referendum in 2015, the “Red Peak” flag got 15% of people to vote for it, when only 6 weeks earlier it wasn’t even included in the shortlist of options. That’s a great example of an idea spread (at least initially) almost exclusively on social media.

However,

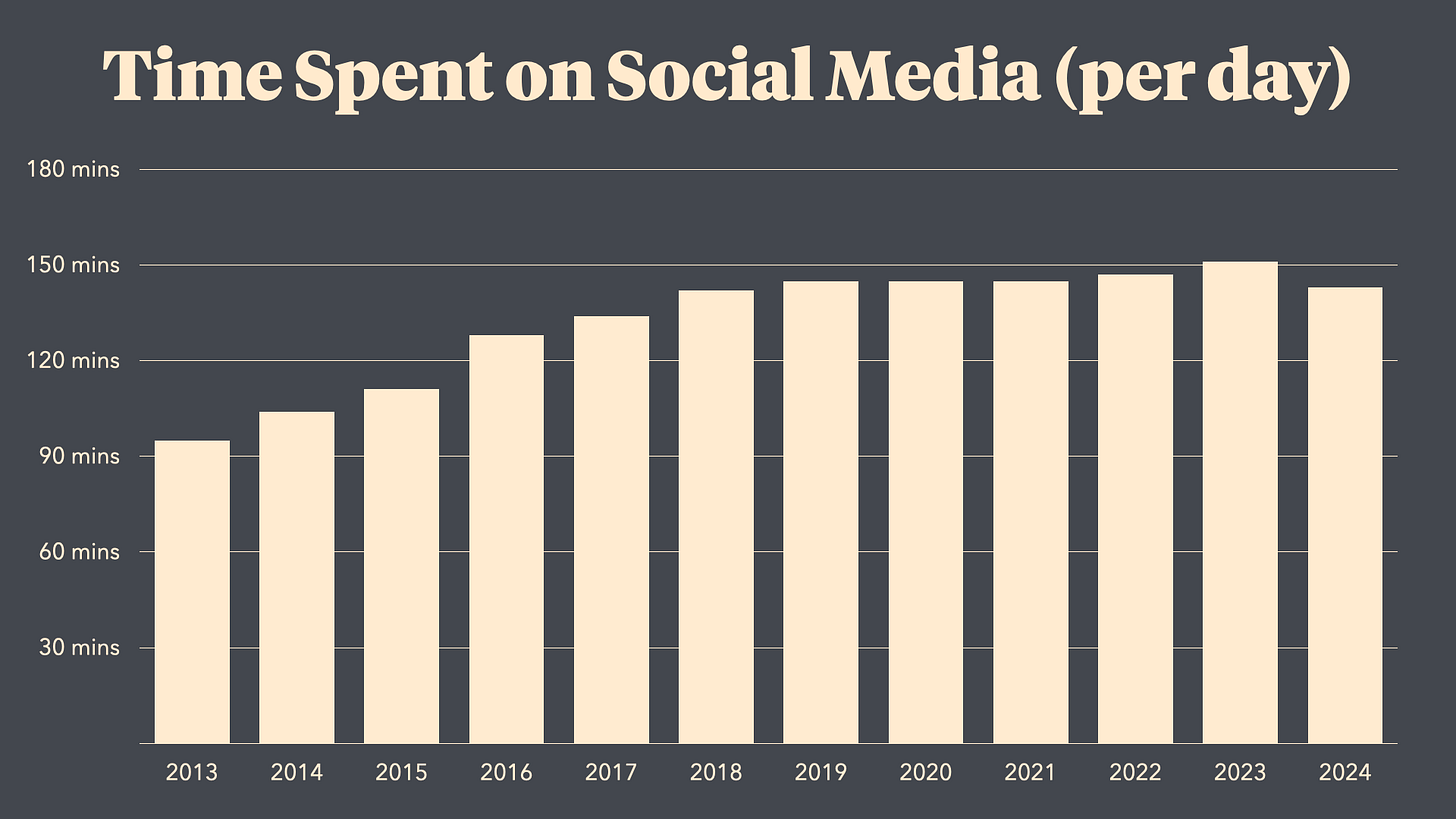

We also seem to be past peak social media. The limit appears to be about 2.5 hours per day. This has been flat since 2019.

Perhaps you still think social networks are technology. But to the next generation they are definitely now stuff.

I think we may need to come up with a new name for “old” media, just like we did with “snail” mail. Increasingly social media is media.

3. Localisation (and personalisation)

The third tidal wave is a bit harder to point at. It goes back even further than the other two revolutions, to the emergence of specialist marketing agencies in the 1950s and 60s (the “mad men” era). The idea is that the more specifically you defined your target market the easier it is to reach them. Technology lets everybody do this much more effectively.

Trade Me is a good example of this. In 2001 we became the North Korea of global auction sites when international sellers were banned, in an effort to reduce fraud. There were a number of features specifically designed to take advantage of localisation: all transactions were in NZ dollars, with local payment and delivery; we added specific local categories, and took full advantage of the two-degrees-of-separation to created a safe and trusted platform.

Trade Me grew over time to include a number of local verticals - Motors, Property, Jobs and later Motels, Insurance, and Daily Deals. Overseas those are all typically successful stand-alone businesses.

The same patterns is repeated with apps like Grab, which is popular in South East Asia. They combine disparate services like taxi bookings and food delivery with payments, couriers, hotels and events. Just like Trade Me, combined into a single app for a targeted local audience.

At the other end of the spectrum are services like Uber, which is a global service which has replaced fragmented and, in many cases inefficient, local markets with a significantly better user experience.

We shouldn’t take services like this for granted. Apps like Uber are popular - but don’t operate everywhere. Apps like Grab are broad - but limited to a specific geography. Especially in small markets like NZ this can create issues

So, all three big trends now maturing. These three things are kinda interesting on their own. But, what makes this especially interesting/scary is the intersection:

For example, the GPS chips in mobile phones significantly increase the personal data that can be captured by social networks, which results in a massive increase in their ability to target advertising very specifically.

Substantial businesses have been built on the back of these waves.

Which is a nice segue to…

🆓 Part II: Business Models

Let’s start with another seemingly simple question:

Q: What is a technology company?

My answer to this is: every company is, or should be. Every organisation should be.

If you disagree try to name one company or organisation that isn’t impacted and potentially disrupted by technology?

This idea is best summarised by this memorable Marc Andreessen quote:

Software is eating the world

The theory is: everything that can be disrupted by software will be disrupted by software. This pattern is repeating in every sector, and as a result creating and destroying large companies.

Perhaps the best example is Kodak, which went from being a headline sponsor of the Olympics to bankrupt and out of business entirely, having been disrupted by the technology in smart phones.

The easiest way to understand the threat is to realise that every app on your phone used to be a separate physical thing: phone, camera, calendar, address book, maps, books, music, your wallet (and the cards in it), television, radio … and many other things.

Certainly technology has eaten the stock market. 7 out of the top 8 largest companies are now technology companies, including Apple, Microsoft, Google and Facebook. Plus Nvidia and TSMC, who make those chips I showed earlier.17

The combined revenue of these top 7 tech companies is now more than twice the GDP of New Zealand.

This is very different to the 80s and 90s when companies like IBM, Microsoft and Intel were predominantly selling to business customers. These new technology companies sell to everybody on earth.

Newer companies, like TikTok, are growing revenues even faster. TikTok now measures quarterly revenue in the billions. But, even more staggering, is how they have increased the amount they earn per user every year. How many of the organisations you work in have revenue of over US$100 per person?

These companies make a lot of money. Part of the reason for that is the wide reach of the mobile devices. But the other part is the business models … so let’s look at some of those.

1. Attention (and intention)

The most prominent business model is companies who are selling our attention (and increasingly intention) to advertisers.

Ad supported content isn’t a new idea. Broadcast television and newspapers have been using that business model for decades. What is new is the scale and quality. It’s now possible to target ads very specifically based on the information these companies have captured about you - both what you’ve explicitly told them and what you’ve implicitly told them through your actions (what you’ve clicked on and watched).

The holy grail of marketing now is finding the right things to target. Ideally something very specific, which lots of people are looking for but nobody is currently servicing. Being good at this is all about data.

The biggest companies in the world used to be oil companies. There is still one of those left in the top 10. The others have all been replaced by data companies.

The data these companies collect about us is massively valuable to them.

If you’re not paying for the product you are the product

Services like Google, Facebook, Twitter and TikTok … their product is us!

We might say we care about privacy, but what we do doesn’t typically reflect that. Many of us are happy to give data away in return for “free” services. This is especially true of younger people.

It’s worth acknowledging there are only two industries that talk about “users” rather than “customers”:

Tech companies

Drug dealers

Addiction is real. In fact, we might cynically say: it’s the goal. There are large teams - for example, those 70,000 people who work at Facebook I mentioned earlier - of very very smart people working to make these applications more addictive, so we spend more time with them and they can sell more advertising as a result. Nearly everything struggles to compete with the dopamine hit we get from devices, notifications, likes, and highly targeted content all tuned by algorithms.

There is an asymmetry here. Most people who use this technology are not savvy users, they just want to talk to friends, or track their run, or share some photos. But behind the scenes there are companies making lots of money by collecting and selling that data. The challenge for governments is how to rebalance + how to match the competence of the tech companies.

The worm is turning on this a little. In fact, all of the major platforms now provide tools to help users regulate their usage - Apple, Google, Facebook + YouTube all do this, for example. But they can’t make people want to regulate their usage.

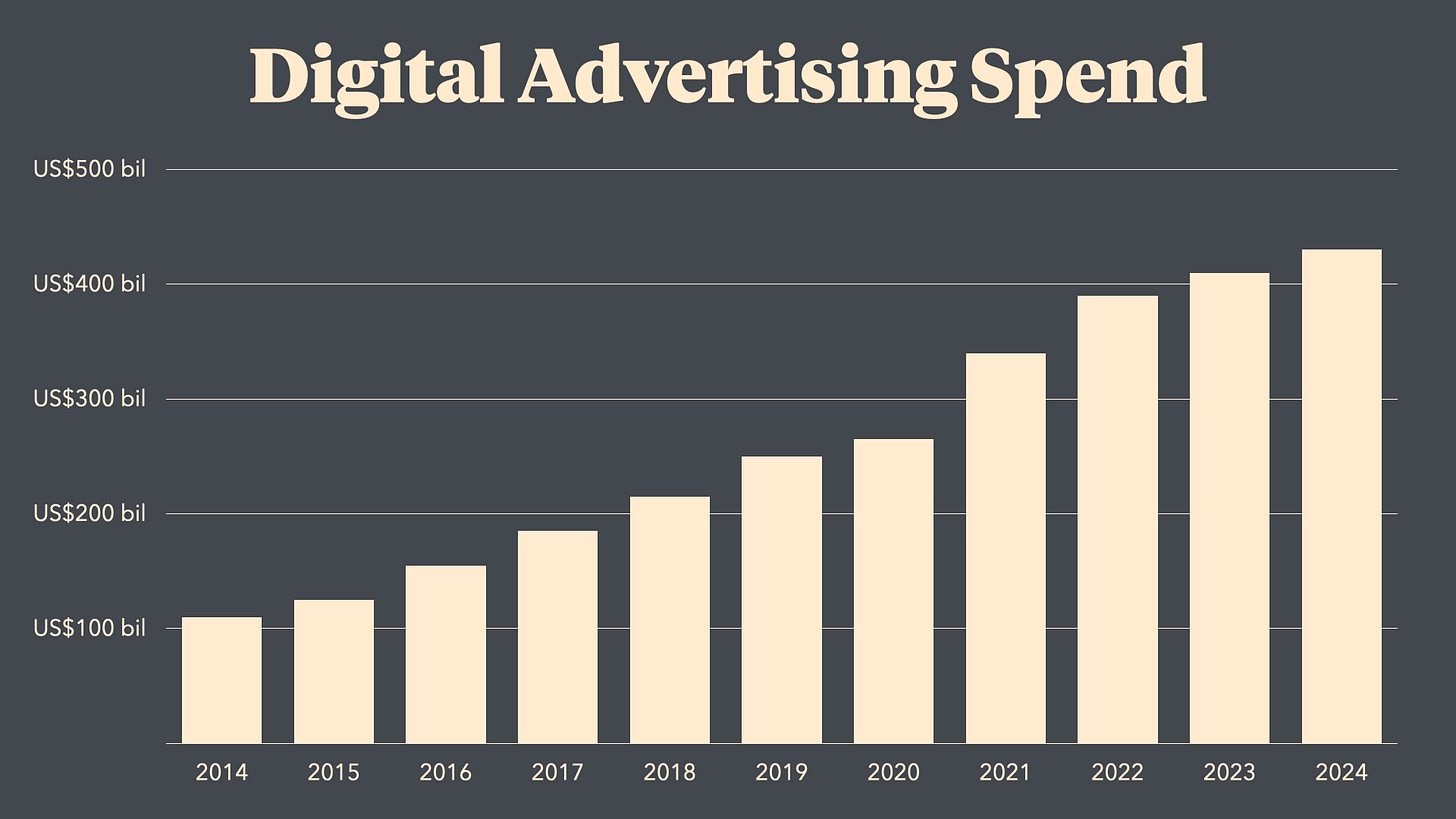

Meanwhile more and more money is spent advertising to people using digital platforms, including by governments. It just reflects the amount of time we’re all spending on these devices.

Q: How are you advertising?

We can all ask this question of our own marketing budgets. How well is it targeted? How much of it is on traditional broadcast media platforms vs. mobile/social platforms? Are you funding the world you want to exist?

2. Subscription

Another popular business model is charging a recurring subscription. Again, this is nothing new. Paying for a service monthly is familiar to anybody who has belonged to a gym.

Tech people do like to draw confusing diagrams and use jargon like “The Cloud” or “SaaS”. But this just means software accessed online and sold on subscription.

This model has been widely adopted by software companies and has broadly replaced the up-front purchase of software.

Just as software is eating the world, so too subscription services are eating the world. Anything that can be sold on subscription will be: personal grooming, razor blades, underwear, toothbrushes and cosmetics - now all available on a monthly subscription.

Again, data is at the core. These services collect as much information as they can and customise their product accordingly. This is how Netflix can confidently spend billions on original programming - they pay close attention to what you watch rather than listening to what you say you might watch, and then extrapolate from that.

Even computer servers themselves are now increasingly purchased on subscription (so-called “platform-as-a-service”) via businesses like Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud or Microsoft Azure. So companies like Xero don’t own their own servers, they rent them. Technology companies get the benefits of this, but many other organisations still see computers as a capital investment - something to buy once.

3. Marketplace

Many of the most profitable “tech” companies (we’re staring to use a looser and looser definition of technology now) are marketplaces. These are platforms connecting buyers and sellers.

So, for example, Airbnb is the world’s largest accommodation company, but doesn’t itself own any beds. It’s a similar story for businesses like Uber, Etsy and Kickstarter.

Trade Me is again a good local example. There are now 100s of millions of dollars of goods sold on the site every year, and Trade Me collects a fee on each sale, but doesn’t itself hold any stock or take responsibility for any fulfilment.

There tends to be one dominant marketplace. Buyers want to be in the marketplace where the most sellers are, and vice versa. Increasingly that’s true globally. Even for local services, it’s no longer safe to assume the suppliers are local.

These market places are built on their reputation systems - like Trade Me feedback. We tell kids “don’t ride with strangers”, but that is literally Uber’s product. However, the reality is it’s safe, maybe statistically safer than traditional taxis, because we all rate every ride and bad suppliers get found out really quickly.

The difficult reality is in a perfect market place the “winner” is the seller who values their time the lowest. This has caused a big change in job security: reputation is hard earned and quickly lost on these platforms, and sellers margins get squeezed as a result.

This is moving well beyond technology now, to the impact it has on people and on society.

Q: Are you building or busking?

We all need to decide: are we building a platform or busking on somebody else’s platform (and paying them a fee for the privilege)?

For NZ: are we selling milk solids or making chocolate?

⏯️ Part III: The Next Wave

There are a lot of predictions about what technology is going to cause the next revolution.

The important thing to realise about everything on this list is none of them have had their a-ha moment yet. They may. They may not.

We’re still in the investment phase of all of them. Significant amounts of venture capital are being burned hoping to create the next break-out success. But so far there is no equivalent to Apple (mobile phones), Facebook (social networks) or Google (targeted advertising).

The closest is Nvidia, for the moment the largest company in the world by market cap, who make chips rather than apps. In other words, we’re still building these platforms. We don’t know if they will float!

Those tidal waves from the last 20 years are all reaching maturity. We have the devices we need, and we already spend too much time (and attention) on the networks that have been built on that platform. But the next wave hasn’t quite broken yet. We’re in “the lull”.

Q: Are you doing all you can with what you already have?

So, if you’re worried about this next wave, my advice is: be more worried about the last wave.

Honestly, if your organisation doesn’t have a solid strategy that takes into account the changes caused by mobile phones, social networks and targeted local advertising, then worrying about AI or robots is a bit like the person who wants to lose weight and begins by stressing about the nutribiotic content of their diet, but still eats McDonalds multiple times per week.

Do the obvious things first - then worry about what the future might hold.

Q: What data do you have?

A great question to start with is: what data are you already sitting on? How are you collecting it? How are you storing it? How are you using it to make smarter decisions? What are the pattens in that data that could be useful or interesting?

The three tidal waves are revolutions that have changed the world. But they’re now mature and almost ubiquitous. To a younger audience these are not technology, they are just “stuff”. If we’re not already leveraging those we’re missing-in-action.

Tech has eaten the world. Any organisation that isn’t a technology organisation will stand out, and increasingly struggle. The business models that tech companies have adopted influence behaviours and impact lives.

And, it doesn’t stop here. There is some potentially exciting technology in the future, maybe the near future. But we’re currently in “the lull”. Anybody telling you they know exactly what is coming next is probably trying to sell you something!

Think about the platform you’re on - are you building or busking?

I will leave you with this simple mantra, which I used to have pinned above my desk when I worked at Xero:

We can expand on that to be “it’s not what the technology does, it’s what people do with it”. What matters to us should be the practical uses of the technology by the people we care about - both things it enables and things it replaces.

Everything that doesn’t work yet, Kevin Kelly

iPhone Launch, MacWorld, 2007

Technology adoption by households in the US, Our World In Data

2022 Annual Telecommunications Monitoring Report, NZ Commerce Commission

2022 Annual Telecommunications Monitoring Report - Snapshot Statistics, NZ Commerce Commission

Trade Me Traffic Stats, SemRush

Transistors per Microprocessor, Our World In Data

Facebook Monthly Active Users, Statista

Facebook Employees, Four Week MBA

Number of Global TikTok Users, Statista

Twitch Watch Time, Twitch Tracker

Largest Companies by Market Cap, CompaniesMarketCap.com

Love this post - I was recently at a software event in Wellington where Judith Collins addressed the crowd. Her refrain was “technology is the answer” (not sure the question then either) and “technology will make you all rich”. How? Well this JC did admit she wasn’t sure, but she knew the answer - technology!

P.S. I think the first quote should be “after” not “before”