Invisible technology

Top Three Summer Series - Part 4

Welcome to the 2024/25 Top Three Summer Series. This is the fourth of six posts to be published through December and January, leading up to the launch of my new book How To Be Wrong in early 2025. Enjoy!

Aim … Fire 8th December

Feedback Loops 15th December

A sky full of stars 22nd December

Invisible technology 5th January

Over the holiday period I also published Three-by-Three, my 2024 Year in Review.

At the bottom of this post you’ll find a link to download the first chapter of the book. Once you've read it I'd love to hear what you think.

🫥 A light bulb moment for AI?

In 1882, Thomas Edison threw the switch at Pearl Street Station in Lower Manhattan, providing electric light to 82 customers in the immediate vicinity. Some saw it as a novelty – a cleaner, safer alternative to gas lighting. Others recognised it as the dawn of a transformation that would reshape civilisation. They were all correct, in their way, but none could have predicted how completely electricity would eventually weave itself into the fabric of modern life. Or how long that would take – nearly 150 years later, we’re still debating the merits of electric vehicles, for example, and many households still literally cook with gas.

Meanwhile, if you believe many of those trying to guess what 2025 has in store for us all, this could, finally, be the year that the machines take over – Artificial Intelligence (AI) will apparently change everything. Whenever I hear breathless predictions like this I think back to Edison and ask: what if the opposite is true? I am, after all, also old enough to remember the warning handed down by the latter prophets Chuck D and Flavor Flav: don’t believe the hype.

As with any new technology it’s sometimes difficult to separate the snake oil from the substance. But here is a reasonably sure bet, assuming that AI repeats the pattern established by every other technology that has come before: we will likely overestimate the short-term potential at the exact same time as we underestimate the longer-term impact. To understand why, we need to consider carefully how transformative technologies actually reshape our world. We can look back, in an attempt to more accurately predict the future.

The early years of the electrical revolution were marked by both wonder and skepticism. Edison's "light bulb moments" captured public imagination, but adoption was slow and uneven. Through the 1880s and 1890s, electricity remained primarily confined to wealthy neighbourhoods and many businesses continued to rely on gas lighting, regarding electricity as an expensive luxury with uncertain benefits.

Here in New Zealand, Reefton became the first town in the Southern Hemisphere to receive electricity in 1888, driven by mining operations. By the 1920s and 1930s this new technology was starting to impact all aspects of our economy: electric milk-separators revolutionised dairy farming, and electric shearing machines transformed wool production. Household appliances gradually freed women especially from hours of manual labour. Broad adoption of radio and, much later, television, connected us much more directly to the wider world.1

Fast forward, and consider how we talk about electricity today. When a new café opens downtown, no one calls it a "technology company" just because they use an electric espresso machine and LED lighting. When a manufacturer improves their production line, the press release doesn't breathlessly announce their "innovative use of electrical power." Electricity has become infrastructure – invisible yet indispensable, powerful yet pedestrian. We focus instead on what's actually novel: the café's unique roasting process (or hipster customer service), or the manufacturer's innovative product design.

But it wasn't always this way. In electricity's early days, the mere presence of electric lighting was enough to draw crowds. People would gather to marvel at illuminated shop windows and electric street lamps. The technology itself was the story, rather than what it enabled. Companies would add "electric" to their names just to seem cutting-edge, much like many businesses today scrambling to add "AI" to their marketing materials.

Based on the frequent questions I’m asked these days, AI seems to have captured our collective attention suddenly and completely, even though the underlying technology has been bubbling away under development for quite a long time.2 The conventional wisdom has shifted rapidly from “interesting research project” to “existential threat” – with people across different sectors all grappling with the opportunities and risks it presents. Among these concerns, job displacement comes up frequently – a valid worry, but one that may take longer to materialise than those hoping to sell us these new tools might prefer.3

This is my response: "We have harnessed a new form of electricity. What are you going to do with it?" To answer this, I like to press anybody who is excited about AI's potential to be specific: what is the most concrete example of how they have personally used it in their work? The responses are telling. More often than not, when pressed, they struggle to give any good examples. They are enticed by the idea of AI, but haven’t really found any non-trivial way to apply it to the things they do.4

Sometimes I hear about experimental projects or basic automation tasks. A marketing team using it to generate copy or digital art for social media posts. A software developer using it to explain complex code. A researcher using it to summarise academic papers. These uses are valuable, certainly, but they're just the beginning – like using electricity merely for lighting, ignoring its potential to power factories, revolutionise home life, or enable modern communications.

More interesting are the people who have realised that the revolution isn’t the technology itself, but the entirely new things that can be built on top of that platform – new products and services we haven't yet imagined. The real opportunity isn't in replacing human work, but in amplifying uniquely human capabilities: medical researchers who uses AI to identify patterns in patient data, freeing up time for deeper analysis and patient interaction; teachers developing ways to provide more personalised feedback for students rather than just worrying about plagiarism; and energy systems engineers creating smart grid systems that adapt to human behaviour patterns.

They understand something crucial: if we simply use AI to automate existing tasks, we risk outsourcing creative work while leaving ourselves with the mundane and repeatable - that would be a depressing outcome.5 Instead, they're starting with specific human needs and working backwards to solutions, as opposed to starting with the technology and wondering what is possible.

AI is an amplifier. But we have to think about what unique talents we each have that can be amplified. In this early phase of AI's development, that distinction makes all the difference.

When pioneering computer scientist Danny Hillis observed that "technology is everything that doesn't work yet," he captured something profound about how we think about innovation. Once something works reliably – once it becomes useful rather than merely novel – we stop seeing it as "technology" and start seeing it simply as a tool.6

Consider autocorrect, a feature so ubiquitous that we barely notice it anymore – except when it fails. For years, it was the subject of endless jokes and frustrations, infamously turning common expletives into references to waterfowl. The technology was just sophisticated enough to be useful, but just unreliable enough to remain conspicuous. Today, powered by AI language models, it has become remarkably accurate. And precisely because it works so well, we've stopped thinking of it as “technology” at all. It's just part of how writing works now.

When we flick on a light switch today we rarely stop to marvel at the miracle or appreciate the productivity gains. The most successful applications of AI will likely follow this pattern – the term "AI" will fade into the background, leaving only the practical value these tools bring to our lives: a more accurate medical diagnostic tool, a more effective teaching assistant, a more efficient energy management system. The companies that succeed won't be the ones that simply add “AI” to their product names – they'll be the ones that solve real problems in ways that become invisible because they just work.

So as we look to the future, don't be dazzled by what might seem like magic. Take the time to understand how it works. Be willing to experiment. You might be wrong, initially, but you’ll learn a lot in the process. If nothing else, this will give you more interesting questions to ask about what is possible. Start with the problems you need to solve, then work backwards to understand how this new technology might help.

Flick the switch, but don’t just stare at the lights in awe – give yourself the opportunity to invent the future.

👥 Ask the audience

The idea of relative success is an idea I will write about in more detail next week. But in the meantime, a practical example to help bridge from two earlier Summer Series posts, where I talked about goals and feedback loops.

One of the things I’ve learned while writing How To Be Wrong is that every time I think I’m 80% done I soon discover the remaining 80% still to go. In recent weeks, as we’ve been putting the finishing touches on the design and layout of the paperback version, there have been thousands of small decisions to make. I was starting to feel weighed down by a few that seemed more consequential than the others. For example, I wanted a memorable book cover, but was labouring the choice, and taking too long to narrow down the options.

I clearly needed to follow my own advice. In the book, I write about how product managers need to prioritise testing with real users. So, I asked Anna from Stickybeak to help me pick a winner.

She helped me design a quick survey that was sent to 200 selected people from NZ and Australia who had purchased a business book in the last 12 months. Each of them was presented with a subset of the options. The results were irrefutable, with just under 50% picking the winning design. As well as the objective data, there was some fascinating subjective feedback in the comments that were captured.

How good?!

By the way, this is something that anybody can do - it’s affordable, you can set up your test online, and you get results fast (days, not weeks or months). If you have your own packaging or marketing messages to test, based on this experiment, I cannot recommend it enough

Note: I’m an investor in Stickybeak and so would obviously love to see many more people take advantage of this service. Get in touch with them today if you’d like to try this with your products.

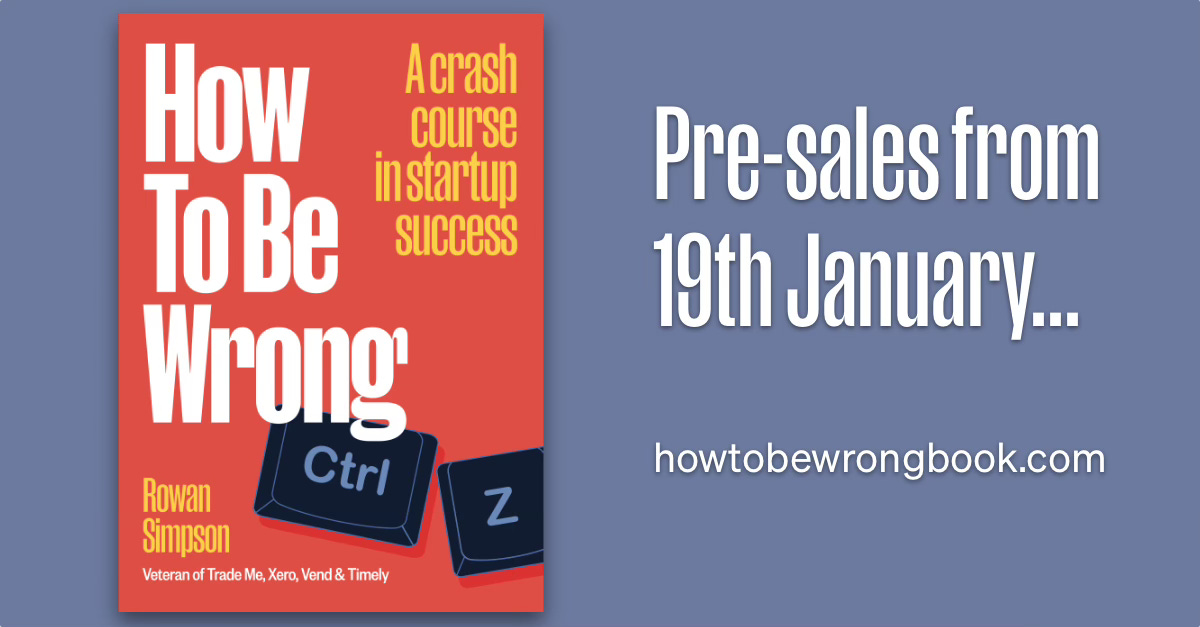

📙 How To Be Wrong: Launch Updates

The response to last week's release of the first chapter has been great. Thank you to everybody who has been in touch with the responses and comments.

For those who haven't read it yet, you can download it now — discover the previously untold stories of near-death experiences at Trade Me, Xero, Vend and Timely.

It starts…

History isn’t fact. It’s narrative.

When a startup business grows rapidly and is sold for hundreds of millions of dollars it’s easy to focus on the end point, and forget about the route. When the stories are re-told over and over, details get re-written or forgotten. And the bits that are omitted and updated are nearly always the stumbles or backward steps. As a result, others starting out on their own venture and hoping for the same outcome rarely hear about these hard moments, and so they’re surprised when it happens to them too. It’s a mistake to assume that it won’t.

🛍️ Pre-Launch Opportunities

For Startups: We're curating a special collection of exclusive offers from innovative startups to bundle with all pre-sale copies. If you have a product or service that would resonate with readers passionate about building great companies, email hello@electricfence.nz with your offer details.

For Readers: Limited edition Ctrl-Z merchandise is now available! The t-shirts and caps feature the distinctive "undo" theme - perfect for those who understand that being wrong is often the first step to being right. There is also a special retro option, if you prefer something a bit more subtle. Discounted launch pricing available for one more week only.

📚 Where to Find the Book

How To Be Wrong will be available in multiple formats: paperback, ebook, and audiobook (coming soon after launch). While I expect most people will purchase it online and have it delivered directly, I also know that many people love browsing at physical shops. If you have a favourite local bookstore you'd like to see stock the book, please ask them to get in touch.

Stay tuned next week for pre-sale details. This book has been years in the making, and I'm excited to finally share these stories and lessons with everybody.

Some early praise for How To Be Wrong:

Every upcoming entrepreneur needs to read this immediately. Not just for the useful specifics, but more importantly, for his practical generosity: an empathetic and pragmatic perspective that is his real super-power.

— Derek Sivers, Author and ex-Entrepreneur (Founder, CD Baby)

I loved the section on metrics... one of the best explanations of how to track useful metrics in a startup of anything I've ever read. I will absolutely be pointing founders to these paragraphs.

— Samantha Wong, Partner at Blackbird Ventures

Rowan is one of the smartest thinkers I have met on the unique potential Kiwi founders have to create globally significant businesses. This book brings extraordinary authenticity to this glossy opportunity while reminding us all that being wrong in a start-up is a necessary part of finding "right".

— Tim Brown, Co-Founder of Allbirds

Photo by Marco Trassini on Unsplash

… and much much later the internet.

Actually my whole professional career - reference COMP307 - Introduction to Artificial Intelligence, which was a paper I completed in the final year of my Computer Science degree, back in the 1900s. A+, since you asked!

As I like to point out to anybody who is frothy about current AI tools: we’re still in the command line era.

I agree with this observation from Simon Willison:

If you tell me that you are building “agents”, you’ve conveyed almost no information to me at all. Without reading your mind I have no way of telling which of the dozens of possible definitions you are talking about.

For example, a team in Spain have used AI to create Aitana, an attractive and very popular social media influencer, who has quickly collected such a large following she even attracted the attention of real celebrities (including one who asked her out on a date). If your job is taking fake photos in exotic locations and creating large volumes of forgettable social media content (aka slop) then you probably should be worried about AI taking your job. I have to admit I’ll find it hard to be sad if that happens.

One of the big unresolved questions at the moment is how much we’re all willing to pay for the use of these AI platforms. The development of AI is predominantly being funded by venture capital and those expenses are not insignificant. Large companies like Amazon and Microsoft have ploughed billions of dollars into ventures like OpenAI and Anthropic (the company behind Claude) A large portion of that cash, interestingly, is recycled into hosting centres and cloud services provided by large tech companies … like Amazon and Microsoft. 🤔 Eventually there will need to be a return on that investment.

Love this comparison with electricity - it feels like you've nailed it (so many electrical puns were deleted in the writing of this comment 💡!)