Getting ahead

Top Three Summer Series - Part 5

Welcome to the 2024/25 Top Three Summer Series. This is the fifth of six posts to be published through December and January, leading up to the launch of my new book How To Be Wrong in early 2025. Enjoy!

Aim … Fire 8th December

Feedback Loops 15th December

A sky full of stars 22nd December

Invisible technology 5th January

Getting ahead 12th January

Over the holiday period I also published Three-by-Three, my 2024 Year-in-Review.

At the bottom of this post you’ll find a link to download the first chapter of the book. Once you've read it I'd love to hear what you think.

🏟️ Zero-Sum

Try to imagine the scene. It’s the early evening of 16th July 2028.1 A hush descends over the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. The large crowd focus their attention on just eight athletes standing at the starting line of the 100m. One by one they are introduced and drop into the starting blocks.

“On your marks”, says the official, pointing the starting gun into the air.

“Set” Briefly, silence, then …

BANG! 💥

Ten seconds later it’s all over. One of the eight athletes is immortalised forever as the Olympic champion. Within a few hours they will be presented with the gold medal, and stand on the dais listening to their national anthem. Two others get the consolation silver and bronze medals for their efforts. The remaining five can only wonder what could have been.2 They quietly file past the media waiting to interview the winners, mostly forgotten like the hundreds of others who have been knocked out in earlier rounds of the competition and didn’t even make it to the start line for the final.

This is one of the remarkable things about sport, and perhaps part of the reasons why many of us are captivated by this type of competition. There is guaranteed to be a winner. But only one.3

We win. You lose. Or vice versa.

But not all things are as contrived as that.

One of the remarkable things about business is there are no guaranteed winners at all - it’s possible that everybody will fail. And at the same time, no reason why there can’t be multiple winners. When one startup is successful it doesn’t detract from the likelihood that another will also be successful - in fact, often the opposite, as lessons learned can be shared.4

In sports, victory is zero-sum. In startups, success is cumulative.

A finite game is played for the purposes of winning.

An infinite game is played for the purpose of continuing to play.— Finite & Infinite Games, James P. Carse

🥧 Baking the pie

One of the things we love to talk about in New Zealand is “getting ahead”. Once you attune to that expression you hear it constantly.

It’s the reward promised to everybody who works hard. And it isn't just a catch phrase - it's a national obsession that shapes our politics and decision making.

Christopher Luxon has said: “I became Prime Minister so that you and your family can get ahead”.

The bit that is left unspoken is: ahead of whom?

When we talk about getting ahead, if we’re honest, we’re mostly only talking about one thing. By far and away the most popular way we believe we get ahead is by owning real estate. The common wisdom is we build our wealth by “getting on the property ladder”. This is an enticing idea. Provided you can somehow jump onto the first rung of said ladder (usually by borrowing as much as possible from a combination of banks and relatives) then over time you’ll be able to climb up the subsequent steps - presumably by buying more properties or more expensive properties or both.

The problems with this are almost never said out loud.

Spending more and more to buy little bits of our country off each other is mostly another zero-sum game.

Making housing increasingly unaffordable for everybody not already on the ladder is an empty victory.

Rampant house price inflation is not wealth creation, it is poverty creation as it makes homeownership less accessible to everyone.5

And, remember, “everyone” in this case includes all of the people who we need to continue to choose to live and work (and pay tax) in New Zealand.

In the last election, one of the big ideas was to make it easier to sell little bits of our country to international investors. As if that is not a one-time sugar hit. Our headlands for their muskets and blankets, all over again.

This fixation has pretty obviously made us relatively poorer, not wealthier. While we've all been busy trading houses amongst ourselves at ever-increasing prices, countries like Singapore have focused on creating actual economic value and seen their wages grow significantly faster than ours.

Consider a “businessman”, who after achieving some financial success invests their savings in a handful of rental properties and then sells them for a profit a few years later. What business are they in, exactly? What value are they creating? What problem are they solving?

We need to redefine what it actually means to “get ahead”?

When Trade Me was sold, it didn't close the door on other opportunities - in fact, the opposite. The capital returned to shareholders and employees was reinvested in dozens of new ventures. The team members who cut their teeth building Trade Me went on to start or join other companies, bringing hard-won experience about what works. Even the technical challenges we solved became lessons that helped others avoid the same pitfalls.

When Xero succeeded, it didn't use up New Zealand's quota of successful software companies - it helped prove we could build world-class products from here. More importantly, it showed that we could take on international competitors in established markets and win. The pathway from startup to global success that Xero pioneered has since been followed by many others.

When Vend and Timely were acquired, it didn't exhaust the pool of potential buyers - it highlighted that companies started here could achieve great outcomes. Each exit created new groups of experienced operators and investors who understood what it takes to build valuable businesses. Many of them are now working on their next ventures, armed with knowledge that can only be gained by doing it once.

I got to see all four of these examples first-hand, working on and investing in these businesses in the early stages. This is why I wrote How To Be Wrong. Not because there's a formula to replicate these past successes - there isn't - but because understanding how we navigated similar challenges can help founders working on their own ventures today to avoid common pitfalls and highlight the patterns that matter. And to highlight the reasons why we do all of this in the first place.

The wealth we create from technology isn't extracted from a finite resource - it's generated by solving problems and creating value. Each success makes the next one more likely, not less.

🤪 Ellsberg’s Paradox

What would it take to convince more of us to invest in startups rather than real estate? How do we warn ourselves off our obvious and harmful addiction to property?

A common answer is: a capital gains tax. But I'm skeptical. Let me explain why…

Ellsberg's Paradox describes how people make decisions when outcomes are uncertain. In a famous experiment, people consistently demonstrated preference for known probabilities over unknown ones - even when the unknown option might offer better odds. We choose certainty over ambiguity, despite poorer outcomes.

This perfectly describes New Zealand's investment psychology. The fundamental problem with our housing market isn't that capital gains on property are tax free. It's that everybody believes those gains are almost certain and that property values won't fall in the long term. Plus, these "sure thing" investments can be leveraged via mortgages.

This is why most people are much less enthusiastic about other types of tax-free capital gains - like investments in businesses. In those cases, both the capital gains and the capital itself are truly at risk. The outcomes, while potentially much much larger, are ambiguous rather than certain.6

Given this deeply ingrained psychology, it's difficult to see how a capital gains tax would significantly change how capital is allocated. Especially if it applied to all investments equally. And even more so if there are exclusions for housing (while even the most bullish advocates of a capital gains tax think the family home should be excluded, there is never any mention of excluding the family business).

If we really want to shift investment preferences - less into property, more into productive businesses - then we would somehow need to make those things we want to encourage seem less risky.7

On the other hand, if we want to make housing more affordable then we need a solution that causes prices to fall. But nobody wants their property value to fall, so any solution that would cause that to happen is considered politically impossible.

Which takes us back to the heart of our problem: The fundamental issue isn't tax treatment. It's that we've collectively convinced ourselves that property investment is a sure thing. We've created a negative feedback loop, that keeps dragging us down. We’ve chosen to get poorer together, while telling ourselves we're getting ahead.

The alternative is building valuable companies that solve real problems. These might offer more ambiguous outcomes, but they are not zero-sum. They are the only way we’ll break this cycle. The sooner we start the better.

“On your marks…”

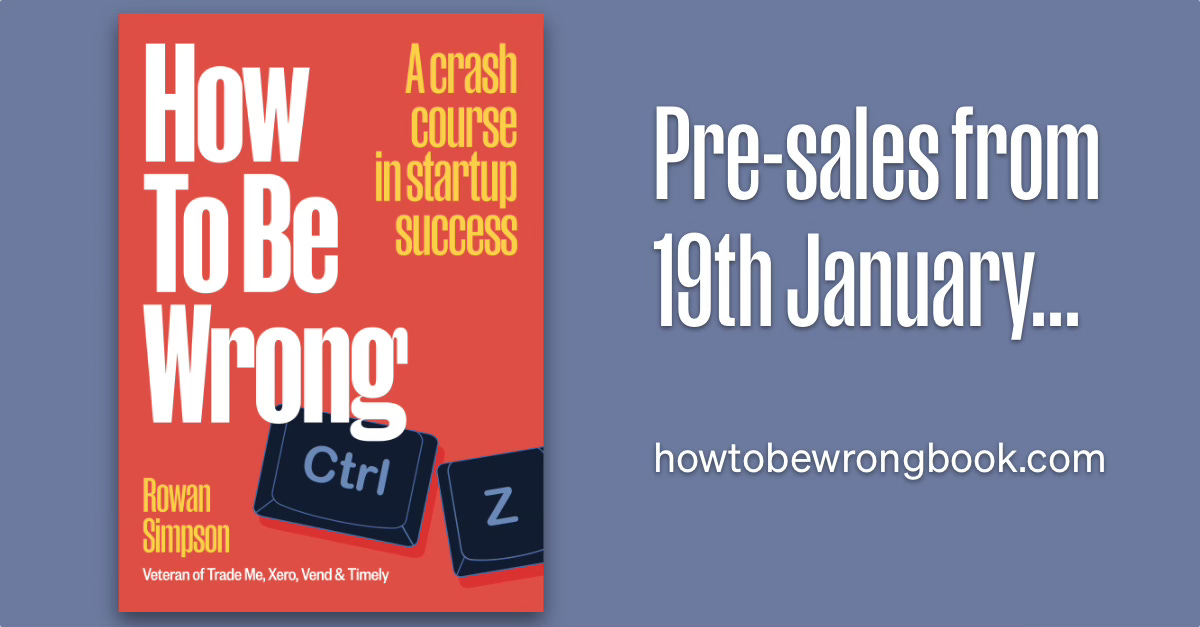

📚 How To Be Wrong

Pre-sales starting 19th January

It’s nearly time… I’m preparing special money-can’t-normally-buy offers as part of the pre-sales promotion, which will be available to buy starting next week. Stay tuned!

I’d also love to showcase your startup to my audience. If you have a product or service that would resonate with readers passionate about building and investing in great companies, I can include a promotion for what you’re building with every pre-sales copy sold. Email hello@electricfence.nz with your offer details.

It’s also not too late to buy limited edition Ctrl-Z caps and t-shirts . The special pricing on these will end on Tuesday this week, so if you’d like one of your own, don’t delay.

This book has been years in the making, and I'm excited to finally share these stories and lessons with everybody.

While you’re waiting, the first chapter is available to download now.

Some early praise for How To Be Wrong:

Last week I shared reviews from Derek Sivers, Samantha Wong and Tim Brown.

Here are some more testimonials:

Rowan has done a very rare double act in life - wildly successful founder and investor. So anyone interested in start-up success must read this. I especially loved his (sometime painful) pearls of wisdom about the roller coaster realities of successful start-ups.

— Sam Stubbs, Managing Director at Simplicity

Founding a startup is often glamorised as all excitement and a smooth ride to success. The reality? It's bloody tough, messy, and far from a fairytale. This book cuts through the noise with a no-BS take, packed with juicy tales from some of New Zealand's most well-known startups.

— Ryan Baker, CEO & Co-Founder at Timely

Exactly the sort of typical boring business-y drivel we've come to expect from you over the years, Dad. I'm sure it will be a bestseller.

— Alice Simpson, my first born child!

Photo: Silver medalist from the Paris 2024 Olympics 100m, Sha'carri Richardson.

By Rowan Simpson.

I’m making up a specific date here for dramatic effect, but there is some method. The LA Olympics are scheduled to run from 14th - 30th July 2028. Unusually, the track-and-field events will be held on the first week of the games, having swapped places with swimming in the traditional schedule. The pool will be installed at the SoFi Stadium - home to the LA Rams and LA Chargers NFL teams - but only after the opening ceremony, hence the delay.

Curiously, there are nine lanes on the 100m track, and in the early heats, quarter-finals and semi-final races there are nine athletes in each race. But for the finals there are only eight athletes included, leaving one lane empty. I don’t know why. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Yes, yes, there are a few examples where the gold medal has been shared by multiple athletes - most recently the men’s high-jump at the Tokyo 2020 Olympics. And, no doubt some of you will read that and wonder where a draw after five days of a cricket test march fits into this theory too. Let those be the exceptions that prove the rule.

The exception to this rule, increasingly common in New Zealand, is when two startups are competing for the same limited pool of people to work on them. That’s the topic for a different post.

The good, the bad, and the reality of falling house prices, by Miriam Bell

Stuff, 10 September 2022.

It is difficult (impossible?) to imagine a property investment that has returned anything close to the 18,822% gains on a share in Xero, purchased in the IPO in 2007 at NZ$1.00 and valued today at A$170.10

Alternatively we could try and make the thing we want to encourage more rewarding. This is effectively the proposal from those who want to see things such as subsidies for startup companies and incentives for early-stage startup investors. The issue with these ideas is that the system is already very generous. The government already funds a long list of such subsidies and incentives. How much are we all prepared to spend to de-risk these ventures and investments even further?

Imagine a different system where we incentivise startup investors by waiving all tax on capital gains. Unlike subsidies currently paid in advance, this would mean that taxpayers don’t take on any of the up-front risk. Plus the benefits flow mostly to the investors who generate the outcomes we say we want by successfully turning startups into high-growth companies. This system would be trivial to implement. The capital gains tax on startup investments in New Zealand is already 0%!

+1 to being sick and tired of the 'we want to enable people to get ahead' mantra.

The truth is most 'everyday' people have zero idea that innovation is even an asset class available to them. Many think startups exits are just about making a founder rich - they don't understand all the layers beyond that which you layout really well here, thanks.

Great article Rowan. Its not easy to change the kiwi mentality, but a significant step forward would be if more Kiwisaver funds followed the example of Booster Innovation Fund and started investing in early stage companies.

And it doesn't help when the media fixates on failures, such as Supie, or when someone tries to innovate in any industry but things don’t work out as planned.