28th February, 2021

Week 09/52

🍔 Layer

Last year I was included in a Covid Oral History project. I recorded 12 interviews during and immediately after the first lockdown.

These recordings will eventually be part of the Alexander Turnbull Library collection, so those of you who are still around long after I'm not here will be able to check them out then. I've been listening to them in quiet moments over the last few weeks. Even just one year later it's interesting to be reminded of the things that were top of mind in those days.

In one of the first interviews I was asked how I thought the internet would cope with the sudden shift to remote work, with the majority of people working from home.

It was a good opportunity to think about the different layers of this question:

Hardware Layer

Do we have the physical network (e.g. broadband network), bandwidth and capacity installed where it is needed? For example, do we have sufficient wifi and/or ethernet connections in the locations where people need to work, so that they have a reliable connection to the internet?

Software Layer

Do we have the tools setup to enable people to work remotely? For example, do we have collaboration tools like Slack, Zoom and (cough) All Hands that allow people working together to communicate smoothly with each other even when they are not in the same physical location?

Cultural Layer

Do we have the habits and techniques in place to ensure that this network and these tools are used effectively? For example, have we agreed what kinds of communications are appropriate for each of the different types of tools we use - what should be sent via email, what should be shared via collaboration tools, what could be a pre-recorded video update, and when do we need people to be available for a video conference, etc?

My answer, for what it’s worth, was that I was confident in the hardware layer and pretty confident about the software layer, but that I was anxious about the cultural layer. I noted that we were lucky with timing in NZ, given the relatively recent roll out of high speed fibre connections to many places. And, as somebody who had worked mostly remotely for 5+ years, knew that the software already existed and was reliable. But my expectation was that everybody would need to quickly learn the etiquette of video calls and, at least initially, would try to replicate familiar offline ways of working using online tools (e.g. long meetings which are mostly one person talking and everybody listening - these are sometimes painful when you're all in the same office, they are terrible when everybody is on video), and exhaust themselves in the process. I think that's mostly what happened.

Thinking about challenges in layers like this is a really useful technique to apply. It helps you quickly identify where the actual constraints might be and narrow in on possible solutions to those.

Often Meatloaf misleads: two out of three ain’t enough!

🔪 Decide

Q: When we’re faced with a difficult Yes/No decision, how do we choose?

I think it's useful to understand if you are “Default No” or “Default Yes”.

These are actually really different schools, and a common source of conflict between people in a group trying to find consensus.

Default No

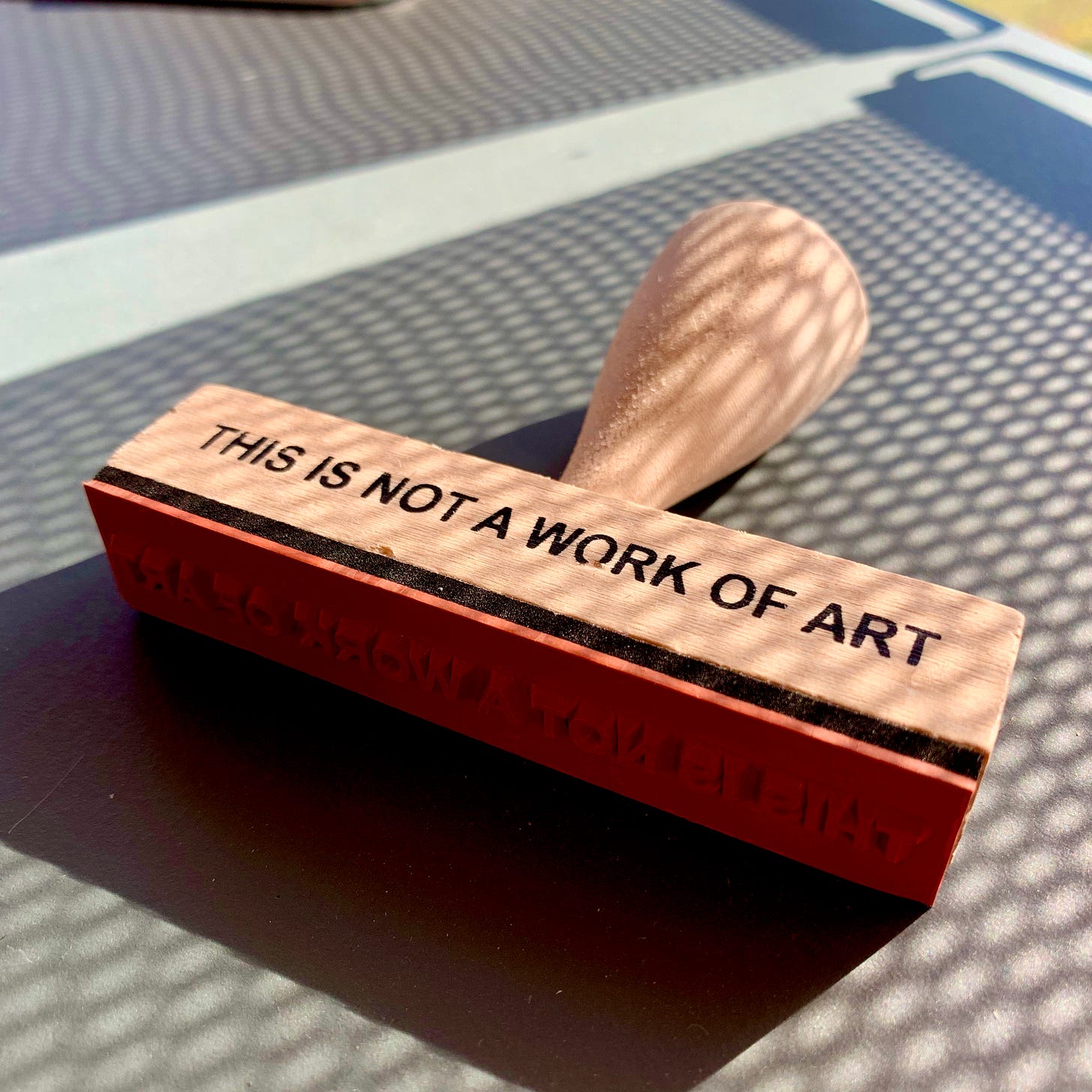

One of the mantras I have semi-permanently on my office whiteboard is:

Focus == Saying No

This is an idea borrowed from Steve Jobs1. It's easy to think that focus means saying yes to the thing you need to focus on. But, actually it's about saying no to the hundreds of other things that would be distractions.

This is the mindset we need when you have too many good options and need to narrow them down, or when we’re feeling overwhelmed and want to make time to complete things.

It requires us to have a high filter on anything new - there is no Yes option, only Hell Yeah or No.

It forces us to be specific about the things that we want: i.e. what evidence do we need to see before you will be tempted to say “Yes”?

It means being willing to miss out on something that might have been good, while we search for something that could be great.

Consider the Latin origin of the word decide: de = off, caedere = cut (same root as incide/incision, to cut into).

Deciding means to cut off other options.

Default Yes

But we can think about decisions very differently, simply by asking: “Why not?”

Or, perhaps more specifically: “What do we have to lose?”

Rather than looking for evidence that might convince us to say “Yes” we simply look for red flags that might warn us to say “No”. And if you don't see them, we keep moving.

This is the mindset we need when we’re not constrained by time and want to maximise our opportunities.

It allows us to take risks that might otherwise paralyse others who are more tentative. It frees us to make a start even when plans are incomplete or we’re not 100% confident about the assumptions we’re making.

Default Defer

Of course, even when faced with a binary decision there is a third option, that is actually very common: “Let's wait and see”.

It's tempting to “Default Defer” because it often feels like we are keeping options open. In some cases it may actually be the right call, but it's important to acknowledge it's neither a decision or a commitment.

If you find yourself stuck like this, it can be useful to ask specifically what we are waiting to see.

It could be evidence (if we’re “Default No”) or it could be a red flag (if we’re “Default Yes”) but it has to be something. Once we’ve defined it then we can think about the steps we need to take to get from where we are now to the decision.

If it helps, it's useful also to realise the risks on both sides of “Default Defer”. If we spend too long searching for evidence or red flags then we’re leaving ourself less time and resources to actually do the thing after we decide to go ahead, or else falling into the trap of a slow “No” if we decide to not go ahead. Neither of those outcomes are desirable.

Warren Buffett has a memorable line on this:

“The difference between successful people and really successful people is that really successful people say no to almost everything.”

I wonder if it's actually more subtle than that:

“The difference between successful people and really successful people is that really successful people understand when it's time to say ‘Yes’ and when it's time to say ‘No’ and hardly ever fall into the trap of saying ‘Let's just wait and see’“

YMMV.

💰 Sell

Some of the best advice I ever got was from a former manager, back in what my kids call “the 1900s”, when I wore a suit and tie to work and starting my own thing hadn't even entered my mind.

I was not having a great time and thought out loud about leaving.

He took me aside and told me “I'm not going to try to convince you to stay, but don't leave because you're frustrated, leave because you're excited about what you're going to do next”.

I took that advice and stayed and spent the next six months or so thinking much better about what I was going to do next. The decisions that I made during that time have shaped the rest of my life.

I've subsequently given similar advice to several founders, trying to decide if they should sell their company. Often the question of a sale has only come up because they have lost their enthusiasm. More than once I've said “Don't sell the company because you're tired. Sell because you're excited about what you can do with the proceeds - at least more excited about that than what you're currently doing with the company”.

Speaking of which … this week we announced that we've sold One Metric.

In one of the first blog posts I wrote about this project when we started in 2018 I said:

There are two things that bug me about the way founders tell the stories about the ventures we're working on.

Firstly, everything is always amazing. We share the polished version of our ventures rather than the honest version. In my experience the reality is always messy and complicated, and often difficult and unsuccessful. But generally heaps more interesting.

The sad thing about that is that when you’re working on a new venture the best you can do is compare your inside with everybody else’s outside. It’s hardly ever an encouraging comparison.

Secondly, we focus nearly entirely on those who have been successful, when we could all probably learn a lot more from understanding the real reasons why things failed.

To the victors the spoils, I suppose, including the opportunity to pretend that they always knew they were going to win. But I’ve learned that even giant successes never feel like that at the time. The outcome isn’t ever premeditated.

I figured both of those things are an opportunity.

As I start on this project, I realise I’m in an incredibly privileged position.

The reason most founders spin their story is often because they are all-in on their venture, and as a result vulnerable. And the reason we mostly hear from winners is because success stories are told in reverse, when the outcome is already decided.

While I’d dearly love for this to turn into a successful thing, if it doesn’t I’ll still be alright. This isn't a double or nothing bet. So I’m free to tell the story. (And, don’t worry, the final post of this blog is not going to be “our incredible journey” no matter what happens!)

Plus, I want to capture it as it happens, before I know the ending. I'm interested in the feedback loops that will create. I think it’s going to be fascinating to come back to later, and compare what I think now with what I think then, and to consider if there is anything I could have done differently based on that. My theory is, like a journal, the process of recording this will actually influence the outcome. Let’s see if that’s true with the benefit of hindsight.

This is definitely not an “our incredible journey” post.

I'm proud of what we built - it was something I wanted to exist in the world and waited a long time for somebody else to build before finally pulling the trigger. But I didn’t quite nail it. I hand it on hoping the new owners will make it much better.

I'm delighted we convinced some other people to use it and hope they continue to get value from it. But never enough to allow it to scale. I’d love to see it be more widely used.

I'm pleased with the financial result. But it doesn't come close to the 🚀 results from some of our other venture investments (I realise that's a pretty impossibly high bar to try and chin and we're not actually competing with ourselves).

Most importantly, given the advice I've dished out to others, I'm excited about our plans for the other things this allows us to focus on.

Stay tuned...

Top Three is a weekly collection of things I notice in 2021. I’m writing it for myself, and will include a lot of half-formed work-in-progress, but please feel free to follow along and share it if it’s interesting to you.

From WWDC in 1997, back when he used to do Q&A and comes from a conversation that traverses the decision to kill OpenDocs and leaking to the San Jose Mercury but settles on a simple piece of wisdom:

I love the advice about leaving when you're excited about what to go to next. I run into so many people who are frustrated and the pragmatist in me always tells them, 'don't leave until you have something to go to'. From a recruiting perspective, it's a sad fact that the unemployed are less attractive to employers than the employed. I'm stealing this line but it's still true, "people want what others have, not what they discarded".